The Gilded Age Makeover: Henry Flagler and the Reinvention of St. Augustine

By the late 1800s, St. Augustine had faded into quiet obscurity — a coastal town with crumbling colonial charm and little economic weight. Then came Henry Flagler. A co-founder of Standard Oil and one of the wealthiest men in America, Flagler saw potential where others saw ruins. With vision, money, and relentless ambition, he transformed St. Augustine into Florida’s first luxury resort destination — changing the city forever.

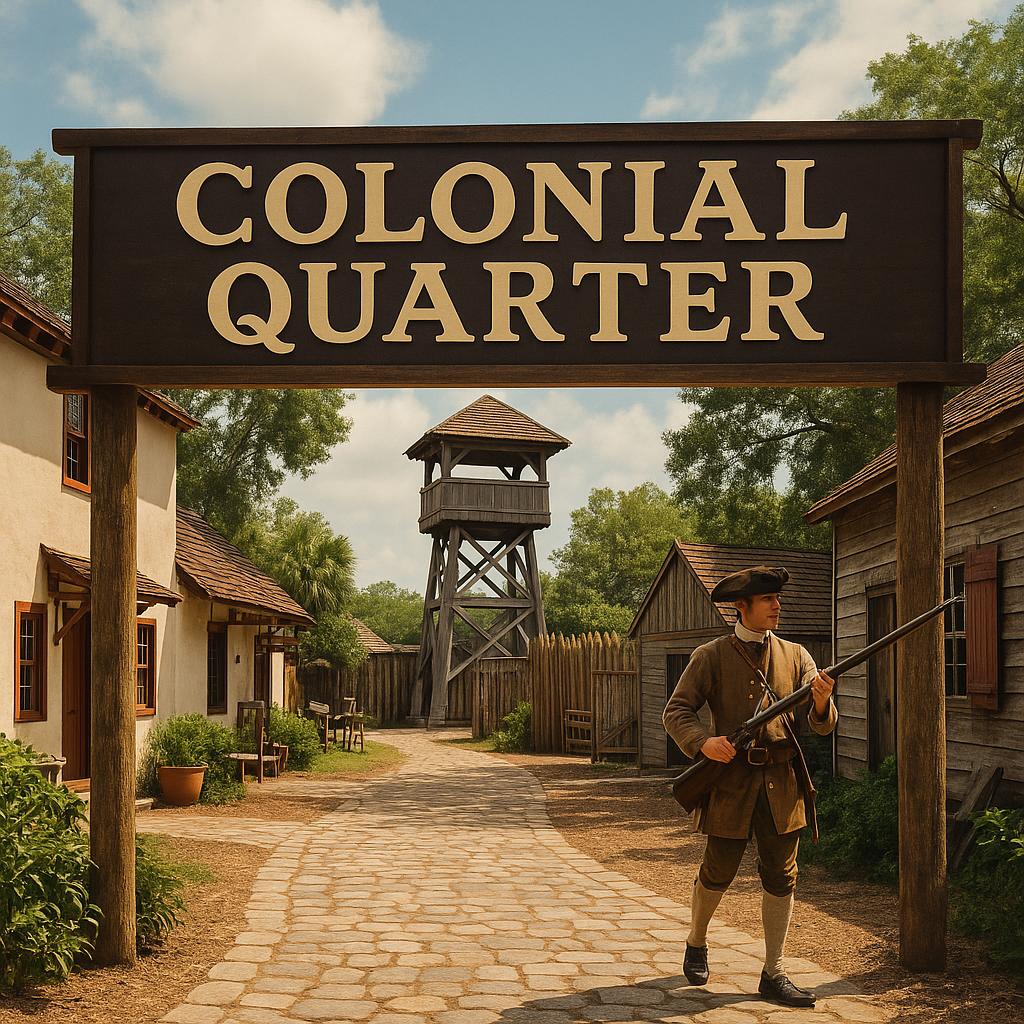

A Forgotten Colonial Outpost

After centuries of Spanish, British, and American control, St. Augustine in the 1880s was old, humid, and rundown. Its historic buildings were in disrepair. The roads were dusty and uneven. The railroad barely reached it. But that colonial flavor — coquina walls, narrow streets, the looming Castillo de San Marcos — gave the city a unique character.

Tourism was a novelty at the time. Northern elites traveled to escape harsh winters, but Florida wasn’t yet on the map. Flagler changed that.

Enter Henry Flagler

In the 1880s, Henry Flagler visited St. Augustine with his sick wife, hoping the warm climate would help her health. He found the climate ideal but the amenities lacking. After his wife’s death, he returned with a new mission: to build a resort town that could rival anything in Europe or the Northeast.

Flagler had two superpowers: bottomless capital and a ruthless focus on vision. He didn’t just want to build a hotel — he wanted to reinvent the city.

The Ponce de León Hotel

His first masterpiece was the Hotel Ponce de León, opened in 1888. It was unlike anything Florida had ever seen — a grand, Spanish Renaissance-style palace with towers, domes, and lavish details. It had electric lights (thanks to Edison), running water, and modern conveniences unheard of in Florida at the time.

The hotel wasn’t just a building. It was a statement: St. Augustine was open for luxury tourism.

Soon after, he built the Hotel Alcazar (now the Lightner Museum) and the Hotel Cordova (now the Casa Monica). He transformed the city’s skyline, reshaping it with Mediterranean influences and Gilded Age opulence.

The Railroad Revolution

But buildings weren’t enough. St. Augustine needed access — and Flagler gave it rails.

He bought and upgraded the Jacksonville, St. Augustine & Halifax River Railway, connecting the city more efficiently with the rest of the country. Wealthy Northerners could now travel comfortably from New York to Florida in days instead of weeks.

The influx of tourists — and their money — was immediate.

A New Identity for the City

St. Augustine quickly became the winter playground for America’s elite. The narrow streets were filled with carriages, ladies in fine dresses, and visitors touring the old Spanish landmarks between rounds of tennis and lavish meals. Flagler restored or rebuilt sections of the historic district to match his vision, blending authentic Spanish elements with dramatic reinterpretations.

The city’s economy transformed. Locals found work in hospitality, construction, and services. Restaurants, shops, and salons popped up to cater to the seasonal elite. St. Augustine wasn’t just a historical relic anymore — it was a modern destination.

The Flagler Legacy

Henry Flagler didn’t stop in St. Augustine. His Florida East Coast Railway eventually stretched down the entire east coast of the state, helping create cities like Palm Beach and Miami. But St. Augustine was where it all began — where the Gilded Age met the colonial past.

Many of Flagler’s buildings still stand today. The Hotel Ponce de León now houses Flagler College, a centerpiece of the city. The Alcazar and Casa Monica are still in use. His influence is baked into the streets, architecture, and identity of the city.

St. Augustine survived centuries of war — and then thrived on reinvention. What was once a colonial outpost became a winter empire, thanks to one man’s ambition and a city’s timeless charm.